- Home

- Deborah Nedelman

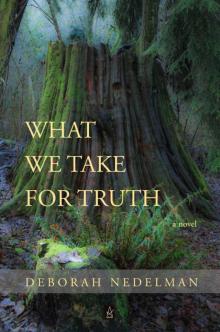

What We Take For Truth

What We Take For Truth Read online

WHAT WE TAKE FOR TRUTH

WHAT WE TAKE FOR TRUTH

A Novel

by

Deborah Nedelman

Adelaide Books

New York / Lisbon

2019

WHAT WE TAKE FOR TRUTH

A novel

By Deborah Nedelman

Copyright © by Deborah Nedelman

Cover design © 2019 Adelaide Books

Cover photo © by Barbara W. Ingram

Published by Adelaide Books, New York / Lisbon

adelaidebooks.org

Editor-in-Chief

Stevan V. Nikolic

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any

manner whatsoever without written permission from the author except in

the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For any information, please address Adelaide Books

at [email protected]

or write to:

Adelaide Books

244 Fifth Ave. Suite D27

New York, NY, 10001

ISBN-10: 1-951214-12-9

ISBN-13: 978-1-951214-12-8

To the forests

CONTENTS

SECTION 1: PARROTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

SECTION 2: CHARLIE

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

SECTION 3: SECRETS

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

SECTION 4: LOST AND FOUND

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Acknowledgements

About the Author

SECTION 1: PARROTS

Chapter 1

May 24, 1991

My dad’s advice: if you’re caught in the forest when a cloud descends, move slow, feel your way. Your eyes are useless. Sound is distorted. You have to trust your instincts.

But now, one instinct says stay still, wait for things to clear and another says everything is falling apart around me, get away.

Could it be easier to be an orphan in the city than it is here? Orphan artist. Alone in the big, bad city.

(Below the last line is a sketch: the skyline of a savage city, buildings roofed with jagged, hungry teeth and a tiny figure in the corner in a red cap, a paintbrush in her hand.)

Grace “Parrot” Tillman opened the drawer of her bedside table, laid her diary inside, and pulled out the tattered bird book she’d inherited from her mother. The cover was torn, the title only partially readable, the pages yellowed and brittle. She ran her forefinger over the faded signature on the inside of the front cover. This ritual of searching out the subtle indentations from the pressure of her mother’s hand had long ago smoothed them away, but Grace still found it comforting. She laid the spine of the book in her flattened palm and let it fall open where it would—the closest she came to an act of divination. The answer appeared as she knew it would: Lilac-Crowned Parrot Amazona finschi (Mexico):Red forehead, lilac crown, green cheeks, pale bill. Resident of western Mexico from southeastern Sonora to southern Oaxaca. A number have been sighted in the San Gabriel Valley of Southern California.

That had been her mother’s dream: seeking those tropical birds, going south to the sun. But despite the nickname her mother had bestowed on her, Grace was a Pacific Northwesterner. The tropics called to her, but a cautious inner voice told her she’d be lost without rain, without evergreens.

A piece of paper, worn thin from handling, slid from its hiding place between the book’s pages and fell to the floor. Grace picked it up and tenderly unfolded it. The crayoned picture of a parrot wasn’t bad for an eight-year-old. For Mommy, From Parrot was printed in childish letters at the bottom. Grace had spent a childhood full of rainy afternoons making drawings of the birds in that book. The sketch pad that lay on the bed beside her was full of more recent efforts to capture the lushness of the tropical fantasy her mother had described to her when she was toddler. Sure, folks had told her she had talent. Even her art teacher at Cooper High had encouraged her to take herself seriously and go to art school. But supporting herself with her art? That was crazy. Grace shook her head, slid the drawing back into its hiding place, and closed the book.

Pulling open the drawer to put the book away, Grace glanced quickly over the slick, wildly colored brochure that lay tucked in the back. Stenciled across the top of the brochure were the words Instituto Allende. That glance was all it took, and Grace was lost once again, conjuring up its pictures of painters at easels and sketchers sitting in front of Mayan ruins, working to capture their faded power on paper. Hugging the bird book close to her chest, Grace whispered “Momma, I wish you were here. I don’t know what to do.”

There would be no answer to her plea. Grace knew this, and she also knew it was time to get to work. Leaving her sketchbook and pencils scattered across her bed, Grace grabbed her jacket and her red watch cap from its hook and headed down to the post office.

The chill bit against her cheeks as she stepped out of the house. She tugged her cap down over her ears and stepped onto the gravel road, the same road she had walked all her life. The recent rush of change, though, had left a ragged wake through the familiar terrain.

The Nybergs, who’d lived next door as long as Grace could remember, had packed up their truck and pulled out two months ago. Already their house had the look of long abandonment. The gutters sagged along the front edge of the roof and black ice slicked the porch steps. Bits of old newspaper and frozen litter were piled up in the flowerbeds where Mrs. Nyberg’s dahlias lay rotting underground.

How many did that make? It was getting to the point where counting the empty houses and storefronts took longer than counting the ones where someone still kept the lights on. Grace held her right hand out in front of her, turned her face away and swept the vision of her neighbors’ empty home out of her sight. As a kid, she’d held her hands over her ears to shut out her father’s angry voice; she’d buried her head under blankets when the scary demons of the dark invaded her sleep. She might be an adult now, but Grace knew that if she allowed herself to feel each loss—let her eyes and ears absorb it—she’d be just as paralyzed as she’d been at four.

Patches of snow huddled in the mucky shade. There was a groggy resistance in the air. On days like this, Grace pictured the green soul of the forest as a defiant teenager refusing to rise from its icy dreams, pulling a gray blanket over its tousled head. The cajoling May sun was not strong enough to win this fight. Grace wanted to believe that spring meant things would improve, but if she were honest, she knew this season… it was a tease, a cheat, and a damn liar.

And yet. This morning the sight of a cluster of yellow tips poking through the dirty crust of ice along the road edge ambushed her. In spite of her eighteen years of experience—of knowing how wobbly spring could be, retreating back into the arms of winter many times before finally setting its course—seeing newly sprouting crocuses made her heart jump. A towhee, hidden in the brush, chittered its suppressed giggle of delight and she was hooked again. She inhaled the frigid air; her shoulders relaxed in the thin rays of sun, and a smile bloomed across her face.

Then she took a single step forward and landed on a transparent veneer of ice. She slid, uncontrolled, until her boot shattered the treacherous barrier, spraying fre

ezing mud into her face.

Dammit! I’ve got to get the hell out of here. Face it— art school in Mexico isn’t going to happen. I could never afford it. Seattle isn’t Mexico, but at least there you can catch a bus instead of sloshing through icy mud to get to your job. There it doesn’t matter if the snow still weighs down the cedar branches in mid-May. Nobody has to race the sun to finish hauling out that last tree before the winter closes the whole town down. Seattle is full of people doing all kinds of things all year long—everyone isn’t a logger or married to a logger!

This thought was like holding the key to a treasure chest in the moment before lifting the lid, when anything was possible. Wiping the mud from her face, Grace sighed. Her cautious inner voice taunted her again, reminding her that the city was more like Pandora’s box than a treasure chest. Yes, plenty of folks had moved away from Prosperity and, yes, she knew some of them had made a life in the city, but the model for escape that burned most brightly in Grace’s memory was her mother, Annie.

Annie had poured her own dreams of running off to exotic lands into the bedtime stories she told her young daughter. But when Grace was four, Annie had disappeared into the shadows of an early death instead. More than disappeared, really. Because after she was gone, no one ever talked about her. As Grace grew, she was haunted by the sense that her mother had vanished not just from the earth but from everyone’s memory as well, so that Grace was left mourning someone none of the other people in town even remembered. In Grace’s child mind a connection formed between the terror of disappearing and the world outside of Prosperity. There lay monsters.

Ridiculous. Here it was, 1991. She wasn’t going to vanish off the face of the earth if she left this town. Prosperity. Even the name of the place was a bitter joke. The only life it offered her was that of a worn-thin wife of a pitiable lumberjack. Her father, Warren, had loved this town and it had loved him back; maybe all he’d ever wanted was to be a logger, or maybe he’d never had any other choices. But Grace was a high school graduate and she had her own dream.

For the hundredth time in the last week, Grace recommitted herself; she was going to get out of here. One more week and she’d be gone. Away from this dying town, these hovering mountains, and all this heavy green. Concrete. Traffic. The buzz of the city. An apartment with her two best friends, the first step to a new life of possibility. With the same gesture she’d used to block the evidence of Prosperity’s decline from her vision, Grace held her hand out in front of her, her fingers spread wide, palm out. With one full sweep of her arm across the horizon, she pushed the images of tropical jungles filled with brilliantly colored birds out of her mind. Seattle was far enough, and Seattle was real.

Standing in front of the small bank of post office boxes a few minutes later, Grace dug into the pocket of her jeans. Her fingers located the metal key ring and tugged it out. It held two keys—one to the mailbox and the other to the door of the Hoot Owl Café. Three miniature plastic birds strung together on a woven cord also dangled from the ring. The largest of the birds, about an inch long, was a green parrot with a spot of red on his yellow bill; he was connected to a tiny black toucan and a mini scarlet macaw. As usual, the cord that held the birds to the ring was wrapped around the post office box key and Grace had to unwind the mess before she could get to the pile of bills waiting inside number 1013.

So many times she’d thought about walking down the street to Sherman’s General Store and getting a new key ring, or at least removing the birds so the keys could dangle free. But she could never bring herself to do either. Her mother had attached those birds and the two keys to that ring. And, despite all the years since she’d last felt the warmth of her mother’s hand, when Grace held on to that ring, she felt connected to her.

Inserting the key into the post office box lock, Grace opened the door and removed the small stack of windowed envelopes. She didn’t look at them; they would only depress her. She wasn’t going to let the state of the café or her aunt’s financial woes make her reconsider her decision. Only one more week of this and she’d be gone!

“Hey, Parrot!” Kev leaned against the post office door. “Got magazines?”

Startled, Grace turned toward the familiar voice. Another sign she needed a change of scenery—Kev, in his perpetual Day-Glo sweatshirt, had become invisible to her. She grinned at him and registered how much the ten-year-old had grown in the last year. Grace had been like a big sister to Kev since he was born; more than once she had cradled him in her arms while his mother begged the doctor for solutions to the puzzles of Kev’s body. There had been few answers, but Kev was one determined kid. Though the doctors had predicted he might never do so, Kev learned to walk, and though school presented major challenges, his memory was phenomenal, and he kept close tabs on all the goings on in town. As long as things stayed constant in Kev’s world, he managed well. When something disrupted the routines of his life, though, Kev and all those who cared about him suffered until a new equilibrium could be established.

Grace knew that her plans to move would rock Kev’s foundation, but she couldn’t let that stop her. She couldn’t stay in Prosperity for Kev. He had parents. He had this whole town.

Grace reached into the back of the post office box and pulled out the Bargreen’s restaurant catalogue.

“Here’s something for you, Kev.” On the slick cover was a photo of a chef smiling behind a glistening stainless-steel cooktop. No need for this. Aunt Jane would just toss it; she’d be lucky if she could manage to replace half the chipped coffee mugs at the Hoot Owl by the end of the year. Kev, on the other hand, would pore over the catalogue. It would occupy him all day.

“Yay! Bargreen’s,” which sounded like “bah gweens” when mangled by Kev’s rebellious tongue.

“OK, Kev. I gotta go to work.” Grace locked up the box and walked over to the door. She held it open as Kev shifted his weight and made his way out of the post office.

“But no school no more! You all done with school now.” Saliva sprayed from Kev’s mouth as he gave Grace a huge grin.

“That’s right. I’m done. Graduated. Never thought I could do it, did ya?” Grace grinned back.

“Maybe, maybe not.” It was Kev’s favorite phrase; he’d repeat it in a mechanical tone whenever he didn’t like what he was hearing.

Grace ignored this comment and waited for him to step down the stairs and out to the muddy street. As Kev walked across the intersection, Grace turned her eyes away from the boy’s awkward gait to look up, over the tops of the buildings into the deep green of the Cascade Mountain Range that hugged Prosperity tightly in its snowcapped grip. There wasn’t much to Prosperity; turning her head from right to left Grace could almost see from the mill at one end to the cemetery at the other. It was a withering nothing of a town only a couple of hours from Seattle. Yet, all her life Grace had heard folks talk as if that journey was much more effort than it was worth. The common sentiment had been, if you could manage to stay in Prosperity, why would you ever go to the city?

Grace didn’t want to think about what she’d be leaving behind: the dew rising from the tops of the trees on a fall morning, making the woods smell like life starting anew; the smooth solidity of the boulders along her favorite mountain trail, where she’d found solace for so many losses; the wild pitch of the eagle’s call as it soared across the valley. But most of all she didn’t want to think about Patrick.

She clenched her jaw, sealing her lips tight. She wouldn’t think about the marriage she’d refused, and she wouldn’t listen to that voice, the one that always asked “what would Momma want me to do?” There was never an answer.

It would be so much easier to leave if it didn’t feel like she was turning her back on her mother somehow. If Grace left Prosperity, who would even think of Annie again?

As she and Kev made their way across the empty street, Grace tried not to notice how the faded blue paint on the front of Jarvis Hardware store was peeling off the wooden siding. But a wedge of memory

managed to slip between the slamming doors of her mind and hold her at nine years old for a brief moment, clapping for joy when Norma Jarvis chose to use a bright color, so different from the drab grays and browns of the other places in town. Things were brighter in general in those days. People were optimistic. The mill was busy. The timber waiting to be cut seemed endless.

No one was going to repaint that building now. Months ago, Tim Jarvis had sold off his stock to Sherman’s and boarded up the windows before he left town.

Once inside the café, Kev settled himself at his favorite table next to the window and spread the Bargreen’s catalogue out in front of him. Grace headed to the back to get her apron. She plopped the stack of mail next to the cash register and pushed through the swinging door into the kitchen. Her aunt stood in front of the sink, scrubbing the pots.

“Nothing important, just bills.” Grace reported this as she opened the refrigerator to find a piece of chocolate cream pie for Kev. His order never varied.

What We Take For Truth

What We Take For Truth